An adapted extract from “Lamarck’s Due, Darwin’s Luck”.

“Thus much then we have gained, that we may assert without hesitation that all the more perfect organic natures, such as fishes, amphibious animals, birds, mammals, and man at the head of the last, were all formed upon one original type, which only varies more or less in parts which are none the less permanent, and still daily changes and modifies its form by propagation.” Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, 1795

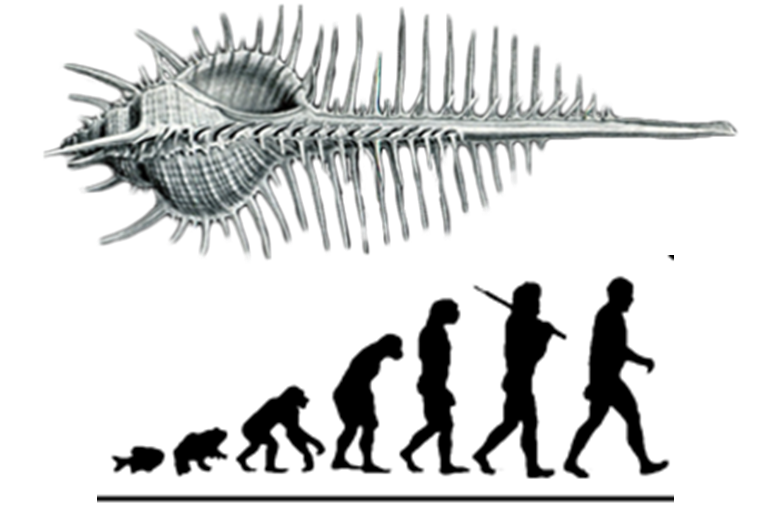

From the general public’s perspective, that early indication of belief in evolution, which was more commonplace than is generally supposed, states the most important aspect of it – that the differences between any two individuals of a species, and the differences between closely-related species, can be put down to minor, accumulative modifications in size and shape of organs and bones. What was unknown in earlier centuries was what caused those modifications. The answer of the most famous early evolutionist, Lamarck, was the effect of the environment, in its broadest sense (including the responsive use and disuse of organs, and sustained changes in diet). Essential to Lamarck’s theory was that minor changes caused by the particular environment in which the organism lived were inheritable – the inheritance of acquired characteristics – and could hence accumulate. (See Lamarck essay) His colleague at the Paris Museum of Natural History, Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, argued in favour of ‘disturbances of the reproductive system’, which could be arbitrary in their effects, as well as being more pronounced. (See Elizabeth Gaskell essay for more about Geoffroy)

Though it is not true, Charles Darwin has acquired the reputation of being the originator of the theory of Evolution by Natural Selection. I am going to take the liberty of assuming you know the gist of Darwin’s theory – that all species are subject to variations which could be beneficial, neutral or detrimental to the organisms that receive them, and Natural Selection sorts them out by rewarding the beneficial and eliminating the detrimental. However, his most famous book did not attempt to explain the origin of the variations upon which Natural Selection operated. Hence it is a supreme irony that one of the most famous books of all time, “The Origin of Species”, has almost nothing to say about the origin of species. Throughout most of the book, he implied that variations were just random modifications, which, by the 4th edition in 1866, he sometimes called ‘spontaneous variations’. That is certainly the reputation that his ‘variations’ acquired, and that reputation has persisted, and been accentuated, ever since. However, every edition of the book contained the following passage (with insignificant modifications in later editions):

“I have hitherto sometimes spoken as if the variations—so common and multiform in organic beings under domestication, and in a lesser degree in those in a state of nature—had been due to chance. This, of course, is a wholly incorrect expression, but it serves to acknowledge plainly our ignorance of the cause of each particular variation. Some authors believe it to be as much the function of the reproductive system to produce individual differences, or very slight deviations of structure, as to make the child like its parents. But the much greater variability, as well as the greater frequency of monstrosities, under domestication or cultivation, than under nature, leads me to believe that deviations of structure are in some way due to the nature of the conditions of life, to which the parents and their more remote ancestors have been exposed during several generations. I have remarked in the first chapter—but a long catalogue of facts which cannot be here given would be necessary to show the truth of the remark—that the reproductive system is eminently susceptible to changes in the conditions of life; and to this system being functionally disturbed in the parents, I chiefly attribute the varying or plastic condition of the offspring. The male and female sexual elements seem to be affected before that union takes place which is to form a new being. In the case of “sporting” plants, the bud, which in its earliest condition does not apparently differ essentially from an ovule, is alone affected. But why, because the reproductive system is disturbed, this or that part should vary more or less, we are profoundly ignorant. Nevertheless, we can here and there dimly catch a faint ray of light, and we may feel sure that there must be some cause for each deviation of structure, however slight.”

This ‘disturbance of the reproductive system’, which is a derivative of Geoffroy’s view, was the origin of Darwin’s ‘spontaneous variations’ – modifications which were undirected and random in their effect, but were nonetheless caused and hence not strictly ‘spontaneous’. In other words, the specifications of each characteristic (e.g. brain size, the sizes and shapes of bones and organs, the distribution of hair and the intensity of colours) were subject to undirected (i.e. positive or negative) internal modifications, at conception or during early development, which could be inherited by subsequent offspring. Since every characteristic (e.g. brain, bones, hair and colours) must once have been a novelty feature, during evolution from an amoeba, their origin too was put down to ‘spontaneous variations’, and they could be beneficial, neutral or detrimental to their possessors. Though Darwin did not clearly differentiate between these two types of variation, I interpret his ‘modifications’ as minor changes in size and shape of existing features, and his ‘spontaneous variations’ as the more detectable ones, including novelty features.

Consequently, Natural Selection is only the guiding system of evolution and not the driving force. The supposed origin of random variations would not be understood for a hundred years. Leaving aside the origin of the variations, Natural Selection is undeniable to the point of being a tautology or truism. Nobody can deny that, if any organism does not live long enough to reproduce, it does not leave descendants. It is also entirely logical that the organisms which don’t live long enough to reproduce will tend to be the ones which are least suited to life or the environments they inhabit. The other side of that coin is that organisms which live long enough to reproduce profusely will tend to be the best suited to life. In order for Natural Selection to be effective and meaningful, it depends on significant over-production of offspring followed by natural culling down to the sustenance level of the environment, as exemplified by the following passage from “The Origin of Species“:

“Owing to this struggle for life, any variation, however slight and from whatever cause proceeding, if it be in any degree profitable to an individual of any species, in its infinitely complex relations to other organic beings and to external nature, will tend to the preservation of that individual, and will generally be inherited by its offspring. The offspring, also, will thus have a better chance of surviving, for, of the many individuals of any species which are periodically born, but a small number can survive. I have called this principle, by which each slight variation, if useful, is preserved, by the term of Natural Selection.“

From Darwin’s perspective, Natural Selection sorted out which individuals live and which die. It was a competition to the death. In his original view, any variation which was so profitable to its possessors that it has become ubiquitous to all members of a present-day species must once have been exclusive to only one individual of a former species. He thought each and every ‘spontaneous’ modification was that rare. To his followers – the neo-Darwinists – that became confirmed, as a consequence of their determination that modifications represented one-off genetic mutations. While some of the descendants of that lucky individual thrived to the point of being exclusive now, the unaffected descendants of all the other members of that former species have been culled out by Natural Selection (though some might have received alternative profitable variations which set them on the road to becoming different present-day species). And that has to apply to every profitable variation that is now ubiquitous to any species. That would involve a vast amount of culling. Such mass culling of the mediocre does occur in plants (mainly as a failure to germinate) and reproductively-prolific ‘simple’ animals, for whom it can easily be seen that any slight advantage possessed by an individual could tip the balance in its favour in its competition with its siblings and cousins, all other things being equal. For any species which does not reproduce significantly above replacement level, it is very unlikely. However, there is another way.

Since Natural Selection operates on variations, and acquired characteristics are variations, it would seem reasonable to suppose that Natural Selection operates on acquired characteristics too. Many of Darwin’s followers have claimed that Natural Selection can only operate on random, spontaneous, internal variations and not upon environmentally-caused variations, because of the need to introduce disparity between the variants. Natural Selection depends on disparity. Darwin himself kept Natural Selection and the inheritance of acquired characteristics separate, originally ascribing much more importance to the former. As far as I am concerned, Natural Selection will operate whatever the source of the variations. Disparity could be produced because different members of a breeding group are exposed to different degrees of the environmental effect or because they respond to the environmental effect differently. Let’s have a look at a hypothetical example of an environmentally-caused variation (which applies equally to a variation caused by use or disuse):

All the members of a particular breeding group would be similarly affected by their environment, so there will be a trend in the direction of the variation for the whole group. Given that there would be a disparate rate at which (and degree to which) different members of this group acquire and successively inherit any new or enhanced characteristic, then Natural Selection will still have a part to play. If the acquired characteristic is beneficial to survival, the stragglers would always tend to get pruned out whilst the leaders would tend to survive. The survivors would breed with each other, so the trend would increase, if and only if the acquired characteristic was, at the very least, not harmful. Natural Selection is guiding the whole group in a certain direction, but without the mass culling of the mediocre that standard Darwinism requires. There could just as easily have been acquired characteristics that were detrimental, or where the trend overshot its beneficial level, in which case the stragglers would survive more easily than the leaders in that direction. The trend would be retarded. That is all that Natural Selection was effectively maintaining: that the brakes were put on bad trends and the accelerator was pressed on beneficial trends. History would not record bad trends, any more than history records the mass culling of the mediocre (as opposed to the mass extinction of the unlucky, usually caused by external catastrophes).

With regard to variations which do not seem to be environmentally caused, such as the darkening of moths in industrial areas (which was prevalent in Victorian England), there is an additional way in which Natural Selection could be aided by the inheritance of acquired characteristics (or vice versa). Any random specific modification of an existing characteristic, however imperceptible, can be in one of two directions – bigger or smaller, longer or shorter, darker or lighter, more or less etc. If one was to suppose, as Darwin was not prepared to do, that there was an inherent tendency to vary in one direction or the other with regard to each specific characteristic, based on what the overall combined tendencies of both parents were, then for any breeding group there would be a bell curve of variants. Reproductive pairings between individuals with opposing tendencies would tend to bring the offspring closer to the centre ground (than either parent had been), whilst pairings between individuals with the same tendencies would accentuate those tendencies (to the point where the effects may become more perceptible). Pairings between individuals with the same accentuated tendencies would further accentuate both the tendencies and effects, but such pairings would be rare in a well-adapted species which doesn’t employ Sexual Selection, since arbitrary pairings would be more likely to be between individuals with different tendencies. Thus the bell curve is maintained. This all depends on the tendencies being inherited, as well as the effects, though the former would be an acquired characteristic and the latter an ‘originally-random’ variation. Let’s see how this would work out in practice in a dangerous, competitive world:

Natural Selection would prune out the most extreme variants in a detrimental direction (which might be both, if the species was perfectly adapted) and preferentially aid the survival of the most extreme variants in a beneficial one. In that case, any surviving individual and its prospective breeding partner would both be a little bit more likely to have an inherent acquired tendency to vary in the latter direction. Natural Selection would have created an overall ‘acquired’ characteristic for the whole group of varying in one direction rather than the other. The bell curve would shift in the beneficial direction and would go on doing so, through time and generations via inheritance, until there was good reason for it to stop, which would mean that opposing tendencies had equalised around an established effect in the middle. The tendencies would not go back to Square One, but they would still either lessen the effect or increase it. The trend for the whole group would be in the beneficial direction, for as long as it remained beneficial, and the whole group would ultimately become perfectly adapted to their environment in respect of every characteristic, which is exactly what the underrated 19thC English ornithologist, Edward Blyth, maintained.(See Darwin’s Influences essay) This amounts to saying that rather than requiring numerous successive modifications over many generations to produce a perceptible variation in Darwin’s world, there could be just one tendency which becomes accentuated in preference to its opposing alternative over many generations in the real competitive world. I rather fancy many people think that is how Natural Selection works, and it is quite plausible with the inheritance of acquired characteristics, but not without it.

The modern science of epigenetics has shown that gene expression is not fixed, and that there are inheritably-adjustable ‘volume controls’ on genes, which means that a species can diverge, ultimately into two separate species, without there being any significant changes in their genetic components. (See Lamarckian Inheritance From Epigenetics essay) All that is required is that there is a barrier to reproduction between the two ‘strands’, usually in the form of geographical isolation – a process which was first championed by the German geologist, Leopold von Buch, before Darwin read his book and claimed to have observed it on the Galapagos Islands. (See Darwin’s Influences and Appendix essays) Hence evolution is not so much concerned with genes as with the accumulated use or disuse of those genes. Natural Selection has been acting on the consequences.